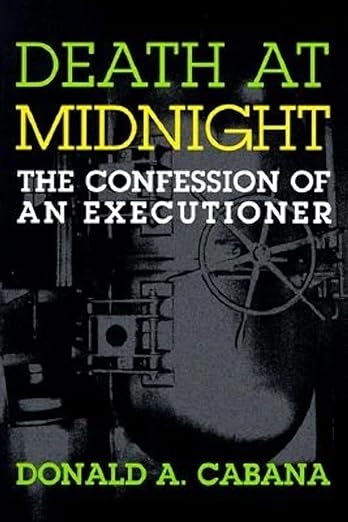

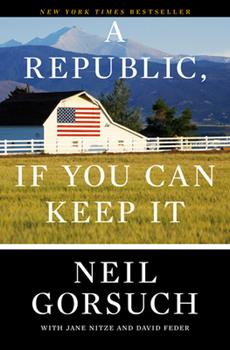

“A Republic, If You Can Keep It” was written by Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch and published in 2019. This book is a collection of speeches and essays with additional commentary, each with some connection to a lesson on the United States Constitution and how the branches of the government work together to create that republic of which he speaks.

“A Republic, If You Can Keep It” was written by Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch and published in 2019. This book is a collection of speeches and essays with additional commentary, each with some connection to a lesson on the United States Constitution and how the branches of the government work together to create that republic of which he speaks.

It is important to note that there is no linear narrative to this book because of the nature of its configuration. It begins with his own thoughts about his appointment to the Supreme Court and the memories he has of his prior experience of being a law clerk; a sort of then and now situation. However, the book will often go from discussing present day politics, to jumping to the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, discussing cases brought before the Supreme Court during those centuries. A large section of the book is reminiscent of a textbook on the United States Constitution, discussing cases and why the given outcome was decided. The book is broken up into sections that each have a purpose: “A Republic, If You Can Keep It” is an introduction for the people who always skip the actual introduction (don’t feel too called out, the phrase “preaching to the choir” is definitely applicable here ), giving the reader a sense of Justice Gorsuch and why his expertise matters; “Our Constitution And It’s Separated Powers” is that government lesson no one remembers learning, but everyone remembers missing the questions on the test; “The Judges Tools” which explores the concepts of Originalism and Textualism in context with various cases and why the concepts matter in deciding an outcome for a given issue; “The Art of Judging” explains what it means to be a judge and how judges make their decisions; “Toward Justice For All” which sounds much less amusing than it actually is, but can largely be boiled down to a conversation on the concept of “justice” and what that means for the American people; “On Ethics and The Good LIfe” which one would expect to be a much more in-depth topic given how it fits with so many of the other sections; and finally, “From Judge to Justice” which brings the reader out of the nebulous concepts and back into the real world.

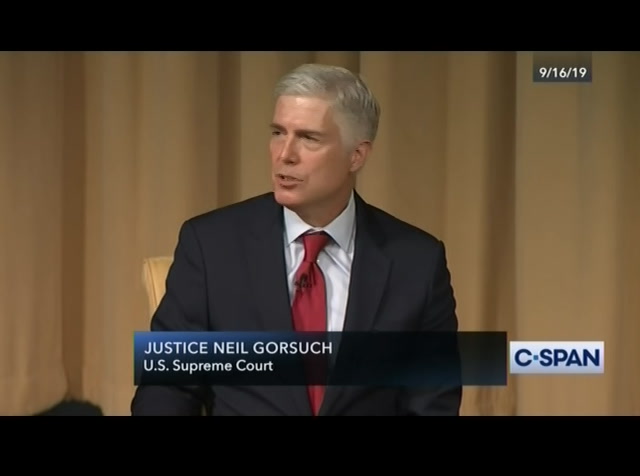

Justice Gorsuch is very well-educated in his field, the very model of a wonk, and it is very obvious that if given any leeway at all, he could spend hours talking or writing about law. A great amount of effort was obviously put into making him appear to be the Everyman; he is the average working American Man one would expect to be living the American Dream. He not only tries to present this image of himself, but also of the other Justices. He comments on Justice Thomas’ “booming laugh” (18), Justice Breyer’s seemingly “endless reservoir of knock-knock jokes” (19), and what can only be described as the nerdiest form of hazing one can imagine— grilling the law clerks on trivia about the Court (19). He mentions Justice Scalia often enough and with enough reverence that there is no doubt that Gorsuch has attained his dream job and is working with whatever the wonk version of a celebrity is (fanboy much, Justice Gorsuch?). This Everyman image is further cultivated by haranguing what is essentially the newest generation about their attitudes towards civility (20- 21); endearing himself to anyone with a “get those darn kids off my lawn” vibe about the next generation. All of this is cleverly done so as to make the reader see him as just as much like every other average American and give himself an extra layer of credibility. In the field of rhetoric, this is called establishing ethos— providing enough context and trust that one is more likely to be open to what that speaker or writer is saying. Essentially, he is priming his audience to be more receptive to his instruction.

Justice Gorsuch is very well-educated in his field, the very model of a wonk, and it is very obvious that if given any leeway at all, he could spend hours talking or writing about law. A great amount of effort was obviously put into making him appear to be the Everyman; he is the average working American Man one would expect to be living the American Dream. He not only tries to present this image of himself, but also of the other Justices. He comments on Justice Thomas’ “booming laugh” (18), Justice Breyer’s seemingly “endless reservoir of knock-knock jokes” (19), and what can only be described as the nerdiest form of hazing one can imagine— grilling the law clerks on trivia about the Court (19). He mentions Justice Scalia often enough and with enough reverence that there is no doubt that Gorsuch has attained his dream job and is working with whatever the wonk version of a celebrity is (fanboy much, Justice Gorsuch?). This Everyman image is further cultivated by haranguing what is essentially the newest generation about their attitudes towards civility (20- 21); endearing himself to anyone with a “get those darn kids off my lawn” vibe about the next generation. All of this is cleverly done so as to make the reader see him as just as much like every other average American and give himself an extra layer of credibility. In the field of rhetoric, this is called establishing ethos— providing enough context and trust that one is more likely to be open to what that speaker or writer is saying. Essentially, he is priming his audience to be more receptive to his instruction.

However, it appears that Justice Gorsuch cannot really decide who his audience is, which is essential for any type of persuasive discourse. (And yes, teaching, instructing, and imparting information fall into the category of persuasive discourse, given that the instructor or speaker has the make their audience care enough to retain any of the information.) The structure of the book explains some of this confusion since it is a collection of speeches and essays, but it is so disjointed in its arrangement that a reader will feel at times mocked for the simplicity of the langue, and other times, completely out of their depth without a more thorough understanding of the way the government works. At times, all the effort that has gone into making Justice Gorsuch appear like the Everyman is rendered nugatory when, through his own tales of his days as a law clerk and reminiscing over the same, the reader is very obviously made aware that those who study the law and pursue a career in the field are part of a society of people who have their own inside jokes, language, communication style, and understanding of the very laws that govern the nation. It is unintentionally othering the reader and pointing out that those outside of the know just wouldn’t get it. Furthermore, the method Justice Gorsuch uses to endear him to some (I.e. traditionalists who believe the world has an incivility problem (19- 21)) alienates many others and gives off those “get those darn kids off my lawn” vibes mentioned previously, making him sound like every middle-aged dad in the south who has exactly four stories to tell and never remembers quite how they go or who has already heard the stories before, resulting in everyone hearing various versions of the stories more than once.

However, it appears that Justice Gorsuch cannot really decide who his audience is, which is essential for any type of persuasive discourse. (And yes, teaching, instructing, and imparting information fall into the category of persuasive discourse, given that the instructor or speaker has the make their audience care enough to retain any of the information.) The structure of the book explains some of this confusion since it is a collection of speeches and essays, but it is so disjointed in its arrangement that a reader will feel at times mocked for the simplicity of the langue, and other times, completely out of their depth without a more thorough understanding of the way the government works. At times, all the effort that has gone into making Justice Gorsuch appear like the Everyman is rendered nugatory when, through his own tales of his days as a law clerk and reminiscing over the same, the reader is very obviously made aware that those who study the law and pursue a career in the field are part of a society of people who have their own inside jokes, language, communication style, and understanding of the very laws that govern the nation. It is unintentionally othering the reader and pointing out that those outside of the know just wouldn’t get it. Furthermore, the method Justice Gorsuch uses to endear him to some (I.e. traditionalists who believe the world has an incivility problem (19- 21)) alienates many others and gives off those “get those darn kids off my lawn” vibes mentioned previously, making him sound like every middle-aged dad in the south who has exactly four stories to tell and never remembers quite how they go or who has already heard the stories before, resulting in everyone hearing various versions of the stories more than once.

If you have any interest in reading what is indubitably one of the wonkiest books ever written, this is the book for you. It would make for great reading for a better understanding of the way the constitution is set up. It isn’t a book for the beginner, as it requires the reader to do a lot of the heavy lifting in terms of understanding the concepts mentioned (e.x., Aristotelian ideas, Originalism, Textualism, the structure of the Judicial Branch, etc.), providing a deeper understanding rather than a beginners. Personally, I found reading this book to be reminiscent of the constitution classes I participated in as a child; while learning something new is always nice, it isn’t always fun. Especially when the person instructing you gives off vibes of “socially awkward master of a single trade.” In short, A Republic, If You Can Keep It (or as I’ve been calling it in my head: A Point, If We Ever Get To It) is an educational read with plenty of real world examples and a few jokes thrown in. If you want a no nonsense book with enough interruptions of legal-ese and law analysis to keep you from falling asleep, this is the book for you, provided you can stay with it enough to fully understand the meaning of the book’s title.

If you have any interest in reading what is indubitably one of the wonkiest books ever written, this is the book for you. It would make for great reading for a better understanding of the way the constitution is set up. It isn’t a book for the beginner, as it requires the reader to do a lot of the heavy lifting in terms of understanding the concepts mentioned (e.x., Aristotelian ideas, Originalism, Textualism, the structure of the Judicial Branch, etc.), providing a deeper understanding rather than a beginners. Personally, I found reading this book to be reminiscent of the constitution classes I participated in as a child; while learning something new is always nice, it isn’t always fun. Especially when the person instructing you gives off vibes of “socially awkward master of a single trade.” In short, A Republic, If You Can Keep It (or as I’ve been calling it in my head: A Point, If We Ever Get To It) is an educational read with plenty of real world examples and a few jokes thrown in. If you want a no nonsense book with enough interruptions of legal-ese and law analysis to keep you from falling asleep, this is the book for you, provided you can stay with it enough to fully understand the meaning of the book’s title.

Nixon’s tenure also saw the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969, which mandated that all federal agencies consider the environmental impact of their actions and projects. This law introduced the requirement for Environmental Impact Statements, ensuring that environmental considerations became a central part of government decision-making.

Nixon’s tenure also saw the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969, which mandated that all federal agencies consider the environmental impact of their actions and projects. This law introduced the requirement for Environmental Impact Statements, ensuring that environmental considerations became a central part of government decision-making.