I’ve spent the last several weeks investigating the issue of police violence, specifically when it results in death. I’ve sat through difficult interviews with the people tasked with pulling those triggers, interviews with the people at the business end of those guns, and with the community occupants left to deal with the remains. I’ve tried very hard to arrive at a clean and easy summation.

[And] maybe even a solution.

The good news for everyone on all sides of this complicated issue [is that] I found it. The good news for my personal friends who occupy such different but strongly-held, deeply-entrenched positions [is that] I found it. The good news for my editor(s) who need a column published on time [is that] I found it. And, most important of all, the great news for my two primary interview subjects, guys whose careers and causes seem to depend on an answer that justifies their very existence [is that] yes, I found it.

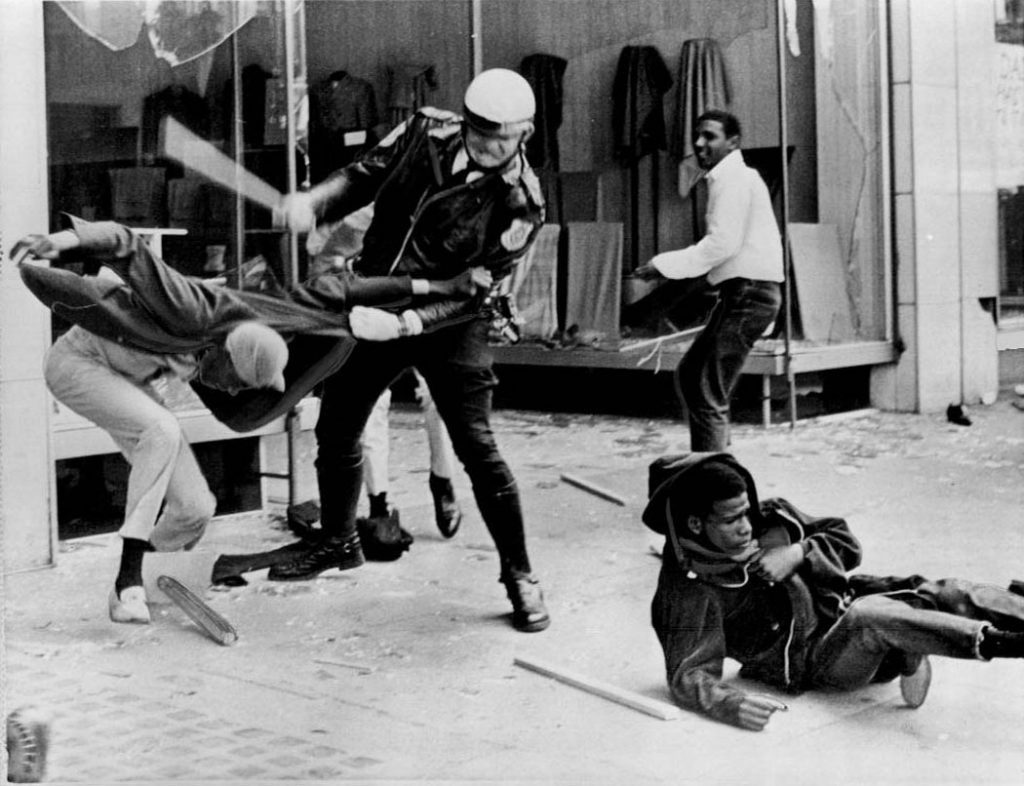

Let’s start at the beginning: Black people are being shot by the police.

No one, and especially no one’s television, will argue against this fact in a winning way. Heather MacDonald in her 2015 book, “The War on Cops” says that African Americans make up 12.3% of the nation’s population, commit 42.5% of violent crimes, and die by gunfire at a rate of 7 to 1 compared with whites. But only 4% of the blacks killed by guns in this country are shot by cops. Unfortunately, almost none of that 4% can help this column navigate these figures today, because almost 100% of that 4% are dead. We see them on the news every day, mostly because we have the ability to see: we’ll get to cell phone surveillance in a bit–but black people…no, screw that; PEOPLE are being killed by cops. Why is this happening, and is it a problem? Wow. We live in a country where we have to ask whether or not people dying is a problem.

I’m writing the wrong column.

So, for the sake of argument, let’s just agree that even one altercation ending in death by cop merits our concern. Even if we try not to think about it, or hear about it, or talk about it, media in all its forms won’t let us look away (not that we should). At any rate, from smaller towns like Ferguson, Missouri, to the largest metro areas in America, like Chicago and Baltimore, news comes at us seemingly weekly of some unarmed black man dying in police custody or at the end of a police firearm. And, right behind each instance comes the protests, the immediate arrival of the Rainbow P.U.S.H. Coalition, Black Lives Matter, and an entire alphabet soup of advocacy groups. This on top of Hannity, O’Reilly, Anderson Cooper, and all the talking heads of cable news with all of their…talking. Outrage; fueled and funded by anger, argument, and accusations. People are dead. People are angry. People want answers.

In all the seriousness and pain of it all, I found it extremely refreshing to watch HBO’s John Oliver a week ago attempt to encapsulate this issue–police shootings–and find levity in it at the same time. The best 19 minutes and 55 seconds of all of the research done for this column was spent watching this. In it, Oliver points out that some of the most basic rights, like the right to vote, are constantly being stripped from African Americans. Then we wonder why they’re mad at authority figures. The Chief of Police in the Baltimore shooting case promised transparency, then refused to release the tape of the shooting, saying, “I never promised total transparency. Transparency is in the eye of the beholder.” Oh, brother. And transparency as an institutional problem? How about the fact that, of the 18,000 police jurisdictions in this country, the FBI does not have complete data on police shootings from a single one. The Department of Justice has admitted to purposefully painting law enforcement officers in a positive light when investigating them for wrongdoing. Oh, and the Mesa, Arizona police chief recently put out an office video encouraging his officers to destroy any documents they had that could potentially compromise them. And an entire industry has sprung up around “gypsy cops,” who move from one jurisdiction to another to avoid punishment for misbehavior. HBO’s Oliver also correctly identifies the difficulty with judges and prosecutors when it comes to police wrongdoing: Just as principles depend on their teachers and bank CEOs on their loan officers (Wells Fargo), justice officials need close relationships with the police; without whom they would obtain no evidence, make no arrests, receive no lab work, and succeed in not a single prosecution. As a result, the police community enjoys the benefit of the doubt.

And the policed community feels the bias.

Bias. Well, only facts and figures can offset the accusation of bias. But let’s skip the work it takes to describe the multitudinous ways that it’s possible to slice this pie and get to the two factors I discovered the most telling: I looked at the number of violent offenders and the prevalence of gun possession in several police jurisdictions. Then I looked at how many stops by cops ended badly. The two cities that sort of screamed at me in my study were Juneau, Alaska, and Jackson, MS. Juneau because of its extremely high gun ownership, and Jackson because of its high percentage of people with criminal records–especially blacks–being stopped. In the case of each city, there seemed to be logical reasons for citizen contact with the police either ending badly, or…ending badly. 80% of residents in Juneau own guns, and approximately 60% of blacks pulled over by cops in Jackson give a justification for taking them into custody (mostly for minor infractions, such as unpaid fines). The reason for Juneau’s lack of violent encounters is that the public is very well-educated on how to conduct themselves and how to interact with the police, including informing the officer of the presence of a weapon in the stopped vehicle.

Hmm…education and compliance…maybe there’s something to that? More later.

![Mr. Lee Vance, [outgoing(?)] Chief of Police in Jackson, Mississippi](https://www.modstate.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Lee_Vance_KH_t670.jpg)

“They got blood on their hands.”

The Chief admitted, of course, that integration into the community by police is a difficult task, that earning trust and helping inform the citizens of the work law enforcement is doing for good is even harder, and that some policies, like “stop and frisk,” are horribly misapplied. But, regardless of misinformation, “90% of the time, cameras will show the officer was not in the wrong.” And that, he says, is a fact. But, even if a citizen feels they are being wrongly stopped, wrongly ticketed, wrongly detained, or arrested, “You’re not going to win an altercation with a police officer. That’s not the place to adjudicate it, or somebody’s gonna get hurt.”

![[ACLU-Mississippi/Blake Feldman (right-bgd.)]](https://www.modstate.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/ACLU-MS-300x300.jpg)

Coming to meet Blake, I expected a policy wonk with a nerdy bent and a chip on his shoulder. Before looking at his bio online, I also expected him to be black. Blake turned out to be a somewhat soft-spoken young attorney–Ok, he might as well be. He graduated with honors from Georgia Law, and takes the Mississippi bar in February–with a deep passion for social justice, and a very kind personality. He also happens to be a Caucasian. When I began by asking him to prove there was a real problem here, he was ready with an answer. First of all, “People in the U.S. are shot by police three times a day on average, completely unique among developed nations.”

Easy enough.

But, here’s the real cause, as seen by Blake Feldman (by the way, I can hardly stand journalists who mistake Excel spreadsheets and bulleted presentations for good reporting):

1) Poverty is too difficult to escape in this country, 2) Police are simply having too many encounters with the citizenry, 3) People have a constitutional right to not have to “clear the streets” in this country, 4) There is no national standard for police training, 5) The legal system has created a modern form of debtor’s prisons, where people can never get free of compounding fines, suspensions, and probation officers’ fees.

“People are in jail because they can’t purchase their liberty. It’s simply pay or stay.”

![American Civil Liberties Union [ACLU]](https://www.modstate.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/American_Civil_Liberties_Union_logo.png)

Blake says, “Not often.”

Ok, so maybe I didn’t really find a solution. Or maybe I did. Fine, look, if you want this issue packaged all nice and easy, here’s your way out: if the police respected individuals’ rights to not be harassed, people wouldn’t die at the hands of the police. And if people always cooperated when they were detained by law enforcement, people wouldn’t die at the hands of the police. Easy, huh? The difficulty is that, for many in the black community, police officers (black, white, or whatever) represent the latest iteration in a long line of oppressive people, policies, and procedures that exist mostly to keep blacks locked up, shut up, and beat down. Can police ever stop being “in” the community, and simply “be” the community, as Chief Vance hopes? And can it happen quickly and cleanly? Or do we just accept a certain amount of dead black men as the price we pay for misunderstanding each other? For what it’s worth, my journey through this difficult maze has led me to at least a few concrete truths: We’d better start talking to each other, stop yelling past each other, and pray this doesn’t just get worse.