What the heck is the “Broken Windows Theory,” and why should I care?

The Broken Windows Theory is a theory that was developed in 1982 by James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling, positing that if small crimes, like vandalism, jaywalking, or littering are prevented, then more serious crimes, like breaking and entering, stealing cars, or assault would be less common. The theory makes sense, but the devil in this case is NOT in the details.

It’s in something called…implémentation.

The only way to stop smaller crimes is to interfere more with people’s lives. Policies like “Stop and Frisk” were put in place based on the Broken Windows Theory, and have led to, let’s just say, problems. As in, people don’t like the police, police don’t like them back, and people get shot. Like cop people and not-so cop people. This leads to two basic approaches: 1) Get Proactive! This approach means cops come into greater contact with the public BEFORE a crime is committed. Contacty stuff like going door to door, introducing themselves, asking if they can help in any way, eating free hot dogs at the 7-11, picking up their free large, one-topping pizza at Domino’s, and flirting with your teenage daughter at Applebee’s.

You see how this can be productive.

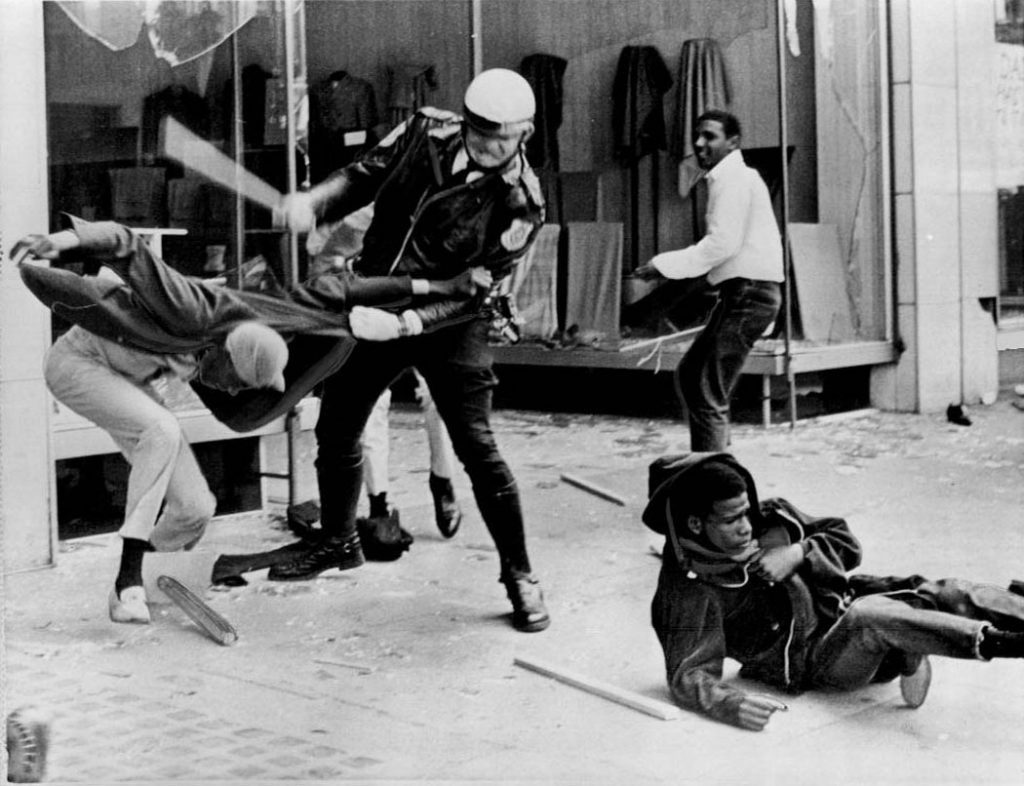

If by proactive, however, we mean police are pulling over more and more people just because they look suspicious, or stopping guys on the street because they’re wearing baggy clothes or sleeping with a cop’s ex-wife, this could result in people, like, getting mad…and getting shot.

What are the pro’s & con’s of Body Cameras? Of Gun Cameras?

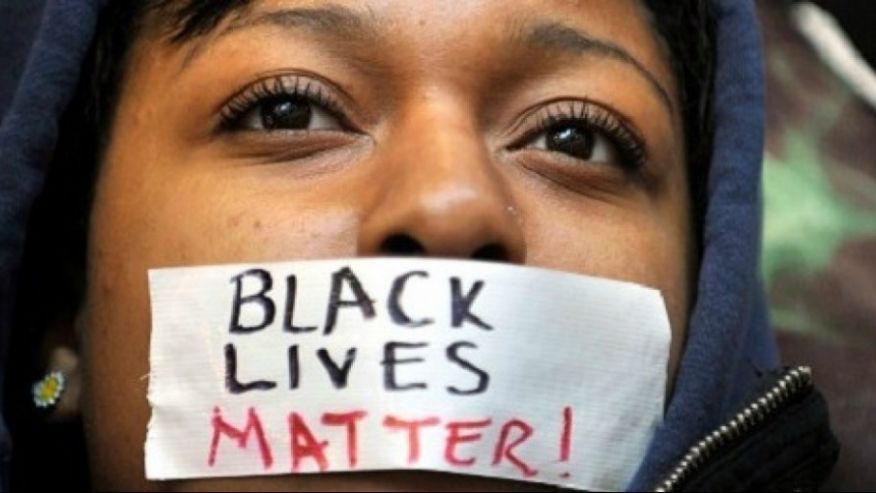

Body cameras (if they’re turned on) can give an accurate record of what occurs during an arrest, and can show the color of the back of the shirt of a black teen when it gets a hole put in it by a white police officer. This also means officers can be held accountable for their actions when interacting with the public. If they follow policy, the body cameras are their best friends. If they don’t, Black Lives Matter show up with Rev. Sharpton. Gun cameras are cameras that are not running until the officer pulls his gun out of its holster. This means battery life is much longer, and it means a camera is on, pointed at the suspect at the most critical moment in a cop’s line of duty. Also, many gun cameras immediately notify dispatch that the officer has his gun drawn, so there’s no need to be distracted with radioing in. The down sides are that the cameras are an extra $500 or so out of what is probably an already-strained budget, and they don’t show the stupidity of the officer or the suspect that led to the gun being drawn to begin with.

What steps could the police and city officials take to improve police-community relations?

I watched a 60 minutes segment a month or so after Bill De Blasio was elected mayor of New York City, who announced at his swearing-in ceremony that he was doing away with “Stop and Frisk.” The tv news magazine was trying to weigh the results of this new policy. The results seemed to be that 1) crime was going up, and 2) relationships between police and the community had been improved. Also, a possible third conclusion was that we haven’t really had enough time to tell what the long-term effects will be.

Police procedures touch every aspect of the community, and how we allow the police to interfere with our lives and how we react to their interference tests the very tensile strength of society’s thread. The police should probably stop or pull over about 20% less suspects than they do currently, and that time should be spent instead fraternizing (yes, I am encouraging fraternizing) with the community, as we mentioned before. Political Beast believes this is not only the most effective tool for fixing tension, but is has the added benefit of being the right thing to do.

What are the pro’s & con’s of allowing police officers to live outside of the municipality they work for?

This is a great question that seems simple enough: should we require cops to live in the communities they police? The upside to allowing cops to live outside their jurisdiction is that you’re more likely to retain good officers, especially if you’re the chief of a large, urban city. Letting your policemen and women move their families out to the suburbs, with bigger houses, bigger yards, and better schools is quite a poignant way to hold on to talent. Also, some officers don’t like living in such close proximity to the people they’re policing. They feel like, after work, it’s time for a break.

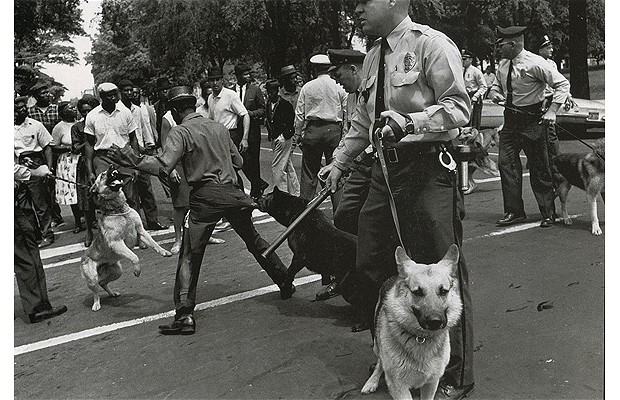

One downside is that, in an emergency, more than half your force could be an hour away. There are, in fact, some suburbs where the police employed by the big city center outnumber the officers employed in the suburb itself. The more insidious problem is that it leads the citizens in the city to feel like they’re being policed by an outside, occupying force. They never interact with the police in any but a negative way, and they never see these officers without a badge and a gun. Similarly, it can lead to a lack of empathy on the part of the police, since they only ever interact with the public in the same negative way.

In Minneapolis, the city has come up with a compromise. Starting out, an officer has to live in the city itself for a number of years, but then are allowed to move outside the city, hopefully after having built those important relationships within the community.

What is the difference between racial profiling and criminal profiling?

Racial profiling is confronting or detaining someone because of the color of their skin. Statistically, minorities commit a larger percentage of crimes, so simply using this easy math, police know they will catch more criminals if they focus on blacks. This is against policy in every precinct in America.

Criminal profiling is looking at the physical situation, location, actions, body language, and speech of a suspect and determining that you have probable cause to confront them. This is what every police academy tries to instill in their cadets. Whether they’re successful or not is determined through the sacred process of suing the pants off any police department that can pay.

What is the “Ferguson Effect” and what can be done to overcome it today?

The Ferguson Effect refers to a situation in Ferguson, just outside of St. Louis, MO, where a supposedly-unarmed black 18-year-old was shot (supposedly in the back) by a white officer. The officer was found not-guilty, after being tried outside the jurisdiction where the shooting occurred, since the court felt he could not get a fair trial because of anger in the community. The effect of the confrontation, the shooting, the trial, and the anger has been that more and more, police officers are choosing not to interfere when they suspect a crime is being committed. This is because of fear of a confrontation becoming an escalation. Thus, more crimes go without scrutiny and (therefore) unpunished.

The Ferguson Effect refers to a situation in Ferguson, just outside of St. Louis, MO, where a supposedly-unarmed black 18-year-old was shot (supposedly in the back) by a white officer. The officer was found not-guilty, after being tried outside the jurisdiction where the shooting occurred, since the court felt he could not get a fair trial because of anger in the community. The effect of the confrontation, the shooting, the trial, and the anger has been that more and more, police officers are choosing not to interfere when they suspect a crime is being committed. This is because of fear of a confrontation becoming an escalation. Thus, more crimes go without scrutiny and (therefore) unpunished.

What could be done to overcome this would be to train better, so that police will feel confident in their investigative skills and prepared to de-escalate better when the situation gets hot. They could also quit being so quick to use their sidearm and readier to use non-lethal weapons, or no weapons at all. But the most important part of this entire midterm exam is what I want to say here: the question is fallacious. It’s based on an assumption that the Ferguson Effect is bad. It isn’t. Political Beast will now attempt to articulate for a third time an opinion that law enforcement should spend less time harassing people and more time getting to know people. Well, the Ferguson Effect takes care of one half of that.

What information of substance can be gleaned from the FBI Report on Law Enforcement Officers killed in 2016 that would be informative to a public and the media who seem more interested in police killings of citizens?

Ok, so nobody asked me this question, but it’s important, so shut up and read:

The FBI report shows that assaults and killings of law enforcement officers has gone up significantly from 2015-2016, and that the most common cause of death is an ambush with a firearm. Obviously, this shows a decreasing level of respect and an increasing level of animosity toward the police. What was the most interesting fact to me was where the report broke down the deaths by age and years of experience. There was very little difference in the rate of attack or rate of death, whether the cop was in his/her 20s with 3 years on the job, or was 45 with 15 years on the job. I would’ve thought that with experience would come caution, and it might, but that also could be offset by complacency.

Let’s be really honest, there’s no simple fix for these and other serious problems. I’m reading James Wilson’s Thinking About Crime, published in 1975, where he develops a series of theories about how to improve policing. Wilson addresses all of these issues. In 1975. Not much has changed, so I hold out no hope that one measly article in an online magazine is gonna crack the nut. What CAN change is if you and I approach community policing the way we should approach our health: we don’t just go in to the doctor and take orders. We ask questions, we do our own research. We become an active participant in our own health care. The same goes for our local police. Don’t wait on them. Walk up and introduce yourself. Learn their names. Tell them what you think. And keep the questions coming.