No, no, we aren’t accusing anyone in the Trump administration of crossing any ethical, moral or legal lines here. Not in this particular article, so don’t get too excited. We’re talking about time-lines. What Political Beast would like to do, in the midst of the guns-blazing rhetoric flying around the famous egg-shaped White House office occupied by the Dealer-in-Chief himself, is to get some sort of perspective on how Trump (and the rest of us) are doing so far since the inauguration a month and a half ago. Like the perspective gained by C3PO and R2D2 at the beginning of Episode IV, walking through a hail of blaster fire to launch an escape pod that gave our golden-bodied protagonist a view that prompted him to exclaim from the pod, “Strange, the damage doesn’t seem so bad from here.” Perhaps. Ordinarily, in this case, we would find someone on the ground with direct information regarding the behavior and performance of the President thus far, then do a solid, unbiased interview, producing hard facts for our readers’ analysis. But let’s alter the deal a bit and instead interview one of the great loves of my life: Madam History.

No, no, we aren’t accusing anyone in the Trump administration of crossing any ethical, moral or legal lines here. Not in this particular article, so don’t get too excited. We’re talking about time-lines. What Political Beast would like to do, in the midst of the guns-blazing rhetoric flying around the famous egg-shaped White House office occupied by the Dealer-in-Chief himself, is to get some sort of perspective on how Trump (and the rest of us) are doing so far since the inauguration a month and a half ago. Like the perspective gained by C3PO and R2D2 at the beginning of Episode IV, walking through a hail of blaster fire to launch an escape pod that gave our golden-bodied protagonist a view that prompted him to exclaim from the pod, “Strange, the damage doesn’t seem so bad from here.” Perhaps. Ordinarily, in this case, we would find someone on the ground with direct information regarding the behavior and performance of the President thus far, then do a solid, unbiased interview, producing hard facts for our readers’ analysis. But let’s alter the deal a bit and instead interview one of the great loves of my life: Madam History.

We’re going to make this pretty straightforward: Trump’s got confirmations hung up in the Senate, a health care plan to pass, and a budget proposed to Congress. That pretty much hits the high points, right? But how is he handling all of this? And how have other modern presidents managed their early struggles? Oh, by the way, you and I could spend the next few paragraphs arguing over when “modern” began, but let’s leave that to the comment section below. We’ll begin with Herbert Hoover. With him began the debate over social welfare, health care, retirement benefits, veterans’ affairs, government regulation, and internationalism, to name but a few. So, agree or disagree, that’s that and here we go:

We’re going to make this pretty straightforward: Trump’s got confirmations hung up in the Senate, a health care plan to pass, and a budget proposed to Congress. That pretty much hits the high points, right? But how is he handling all of this? And how have other modern presidents managed their early struggles? Oh, by the way, you and I could spend the next few paragraphs arguing over when “modern” began, but let’s leave that to the comment section below. We’ll begin with Herbert Hoover. With him began the debate over social welfare, health care, retirement benefits, veterans’ affairs, government regulation, and internationalism, to name but a few. So, agree or disagree, that’s that and here we go:

President Hoover (1929) had an extremely easy go of it with his administration nominees. A Republican majority comparable to Trump’s, combined with President Hoover’s decade-long record in federal service, led to quick approval of most of his picks for cabinet. But Hoover’s signature issue, creation of a Federal Farm Board to stabilize agriculture prices, found stiff opposition from conservatives in his own party (just like Trump’s health care bill). In the end, Hoover responded by calling Congress back to Washington for a Special Session, and held them there until a compromise was reached. Later events ruined this president politically, but we’re talking early-on here.

Boy, oh boy, is this next one tough to fit into one paragraph. It’s only possible if we remember that Franklin Roosevelt (1933) didn’t pass his entire famous (infamous?) alphabet soup of federal programs all at once. In the beginning, the Works Progress Administration was his top priority, unleashing 3 million unemployed men to help rebuild America’s infrastructure and to help renew deforested land in the West. Considering the state of the nation at the time, it is no surprise this piece of legislation flew through Congress. Maybe this is a special case, but remember: FDR was pushing through a costly program based on a new paradigm: that the federal government is responsible for shoring up the American economy in times of depression or crisis. Roosevelt depended on his vibrant, positive personality to get this done, not so much on his ability to wheel and deal. Oh, and his nominees were passed as a formality. Great Depressions tend to have that affect, even on petty politicians.

Another strange case for examining early presidential performance is that of Harry Truman (1945). Taking over during a World War, after the death of an extremely popular President, sorta guarantees you approval of your agenda, at least for the first year or so. Plus, Truman kept all of Roosevelt’s cabinet members, appointed no Supreme Court Justices until late in his term, and focused almost entirely on WWII. Let’s skip this one. Unless Trump ends up in a global state of total war soon. If that happens, Political Beast promises to file an addendum. Yeah, so…

Dwight Eisenhower was a respected war hero and established bureaucratic manager, but he did represent a sea (and political party) change when he took over in 1953. His nominees to cabinet hailed from all corners of the lower 48 states and from both major parties, so they were more or less accepted quickly, something to consider in light of the current president’s proposed hardline conservative characters. As for agenda, peace for Dwight D. was numero uno, and not just peace in Europe, but future peace with the Soviet Union. In the light of Stalin’s recent death and the end of hostilities with Germany and Japan, one would think this an imminently achievable and desirable goal. Not quite. Among many on both sides of the aisle in Congress, President Eisenhower’s budget, with its increased funding of cheap, mid-range nukes and de-funding of traditional military hardware and manpower, Ike’s plan was considered dead on arrival. Yes, yes, just like Trump’s budget today. Eisenhower was mostly successful in getting what he wanted, but not by strong-arming (like Hoover), or glad-handing (like Roosevelt), but by an endless willingness to compromise. It could be argued this compromising almost led to a nuclear crisis later-on, but, again, we’re not talking later, we’re talking early.

The winner of the 1960 Presidential campaign, Richard Milhous Nixon, didn’t get a chance (at this time) to show how he would handle his first months in office, thanks to Mayor Richard Daley of Chicago and a Senator from South Texas, Lyndon Johnson, each of whom contributed to the stuffing of a sufficient number of ballot boxes to see John Fitzgerald Kennedy sworn in as President in 1961. With less than half the nation behind him, JFK took an interesting gallop coming out of the gate. Even in his inaugural address, he emphasized service by this nation’s citizens for each other, and for the planet as a whole. Far from engaging early in the controversial issues that fueled his debates with Nixon, he pursued first the creation of a Peace Corps to spread democratic values and non-military service to others around the globe. The Peace Corps for several decades was a force for good and for good-will in the world, so we count this as a success, although the Bay of Pigs fiasco (only a couple of months into his term) sort of overshadowed this early achievement, but let’s not get distracted. If The Donald had surprised all of us by starting out suggesting a scholarship program for Americans learning Arabic, in order to cross the cultural divide, perhaps Congress would be on board. Or perhaps not. As for Kennedy’s nominees, by the way, solid Democrat majorities at the time greased the wheels that rolled President Kennedy’s nominees through Congress at a rapid clip.

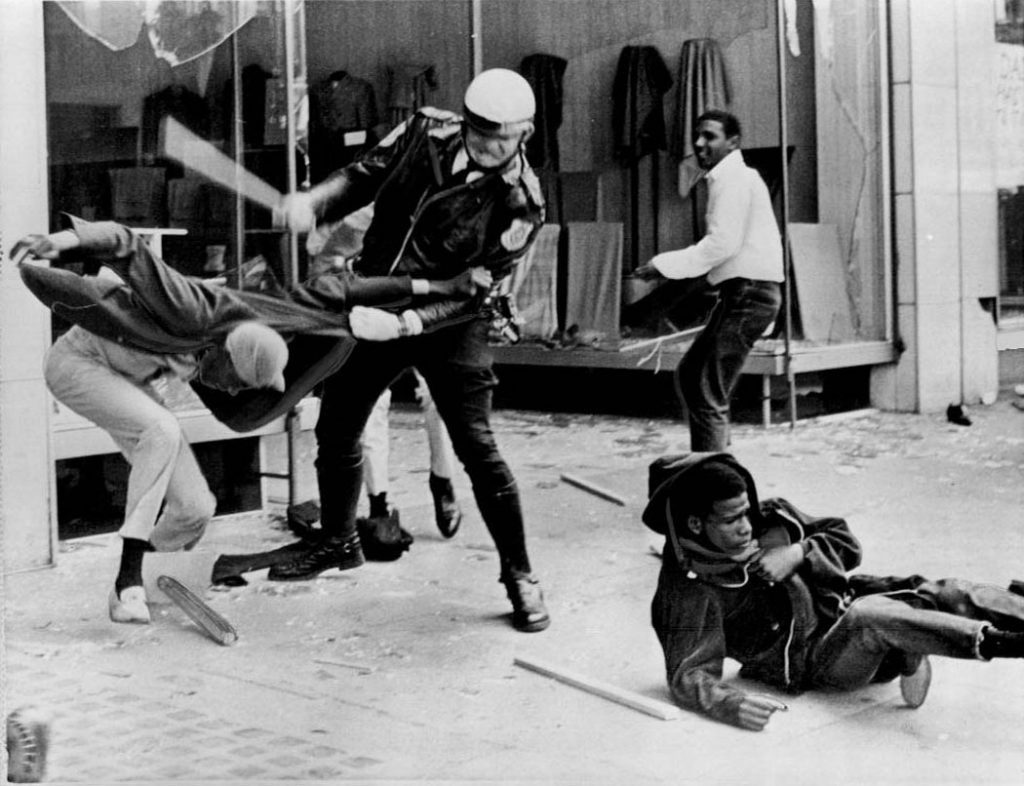

Johnson (1963), like Truman in ’45, took over in odd (read: tragic) circumstances. Like Harry, he kept the cabinet he inherited, but, unlike Harry, he embarked on a rapid and radical legislative undertaking that gave us the Civil Rights Act, Voting Rights Act, and Medicaid/Medicare in short succession. While these were not passed for more than a year, the bills themselves were proposed almost before JFK was cold. And they WERE passed eventually. Whether or not LBJ could’ve gotten this done without the corpse of an assassinated president still fresh in everyone’s mind is debatable, but the President’s famous “Johnson Treatment” was still employed to great affect in the halls and elevators of Congress, with or without the momentum from JFK’s assassination. Would hardball tactics (like locking Congressmen in a room and turning off the air conditioning in the middle of summer until they agree) work for a president like Donald Trump? I dunno. Do you?

Ah, yes. Back to 1960’s big winner: Dick Nixon. A few bored years as a name on a shingle at a major law firm in NYC, one lost California Gubernatorial campaign, and a once-and-for-all-farewell-to-politics speech later, Tricky Dick (1969) is back. Nixon was elected at an interesting time for party politics in this country–as if party politics is ever non-interesting–and his cabinet nominees experienced this firsthand. Announced in December, his entire cabinet, minus one (that all-important Interior Secretary pick) were approved by Congress the day Nixon was inaugurated. In 20 minutes. The reason I mention the interesting state of party politics is because the President at this time enjoyed massive support among southern Democrats, along with healthy enthusiasm among quasi-liberals on both coasts, in both parties, so labels went more or less by the boards, and this particular President enjoyed an easy time at first. This easy time was reinforced by Nixon’s primary concern and primary action: to get out of the country. It’s long been an accepted presidential adage that, “At home, half the country is against you. Abroad, all the country is with you.” On his tour of France, England, Belgium–home of the U.N.–and the Vatican, the President shone, buttressing our allies’ confidence and his support back in Washington. What if today the well-recognized comb-forward was seen bouncing around the capitols of Europe and Asia, instead of bouncing behind the podium at rallies here in the States? Not making a judgment, just thinking out loud.

After accepting (barely) the reality of impending impeachment, President Nixon made a once-and-for-all exit from politics–for real this time–turning the Presidency over to Gerald R. Ford in 1974. Here the broken record once again plays the tune of a president taking over unexpectedly and keeping the cabinet intact, so no controversy there, but ooo, la-la! Controversy ensued on other fronts almost at once. The pardon of former-President Nixon was Ford’s first order of the day, followed by the decision not to intervene as South Vietnam fell to the communists. These were presidential prerogatives, not legislative proposals, but it does make one think: even with a strongman like Trump in office, we haven’t seen this sort of exercise of raw presidential power so far. It fell to a friendly, popular, mild-mannered gentleman like Gerry Ford to pull Oval Office stunts like this. Hmmm. Well, before moving on, it’s only fair to point out that Ford’s first major legislative item was a sweeping arms-control treaty with the Soviets, which was passed with ease by the Senate, but mostly forgotten amidst the anger over Nixon’s pardon and the fall of Saigon.

Pardons again were the first order of the day for the president that would return us briefly to Democrat rule in 1977. And these pardons were every bit as unpopular as that of Mr. Nixon by Mr. Ford. It seems strange now to think that a man as personally popular as Governor Jimmy Carter of Georgia could squander that popularity as quickly as President Jimmy Carter actually did. Like Ford’s first acts, Carter’s were executive orders, first an act pardoning all Vietnam draft-dodgers, followed by a televised scolding of the American people for their wasteful energy usage practices. These burnt up the last scraps of confidence in the imagined leadership at the end of Pennsylvania Avenue, and, as with Ford, overshadowed Carter’s successful peace treaty work, forged between the US, Egypt, and Israel. It’s more than a little interesting that the Trump inner circle has been struggling with potential pardons itself, but has decided to hold off. We’re talking about Ed Snowden, Julian Assange, and Hillary in particular. Would these pardons hamstring the White House as it did in the ’70s, or are the circumstances markedly different? To wrap up with Carter, though, perhaps it was because most of the cabinet had been in place for at least 8 years, or maybe because they were not well-beloved (or both), but at any rate, Carter didn’t have to wait long for all of his nominees to be confirmed, but for that lone HUD candidate, and even she got in after a bit of wrangling. Guess Congress was ready for some new faces. Sorry, Kissinger.

After a fairly swift nominating process (Robert Bork was unsuccessful at being confirmed, but later-on), the next president on our list made his first order of business slashing federal entitlement spending, cutting taxes, and funding a massive military buildup. But there’s one marked difference between Ronald Reagan (1981) and Donald Trump today. While Trump is busy dodging bullets from MSNBC and CNN, at this time in Reagan’s presidential career, he was busy dodging bullets from the end of a .22 pistol wielded by John Hinckley, Jr. The President was successful at dodging 3 out of the 4 bullets fired. A success, I think (though Reagan never tweeted about it). At any rate, surviving this assassination attempt did wonders to propel Reagan’s signature legislation through an unfriendly legislative body. Setting aside Political Beast’s bent toward the jocular for a moment, we will not make any suggestion that pistols and presidents should ever be brought together in such a way, even if it leads to success in battling Congress. And this article is, in part, an attempt to find other, less-violent routes to that same success, so we will proceed.

While some of the presidents described above kept their inherited cabinets, Bush I (1989) kept the men, just not in the same positions. By simply shuffling the deck, H.W. put his own mark on the White House power scheme, while avoiding the need for new Senate confirmation hearings. Pretty darn clever, but then, that describes the elder Bush’s presidency fairly well. Except for the part where those pesky tax increases got him beat by Clinton in ’92. Or was that loss all just because of Ross Perot? Whatever the case, loss was how George H.W. Bush exited. How he entered was with great fanfare, few Senate delays on his nominees, and a litany of stated goals achieved in his first 100 days. How did he accomplish massive increases in DEA spending, aid to former Soviet-bloc nations and a slash in capital gains taxes, and all so quickly? Here’s how: by successfully negotiating a complex and comprehensive compromise budget with a Democrat Congress. You see, Bush the elder believed in accomplishment through consensus, not executive fiat, flattery, or force. This approach served him well in the beginning, although it led to his eventual rejection at the polls, as Congress refused to continue compromising without increases in overall tax revenue. In light of this, Trump seems to be taking somewhat of a middle ground, by saving some of his more controversial aims for next year’s budget, instead of laying it all on the line now. Congressional election year might (or might not) be a better time for a meeting of minds. We’ll see.

After winning the presidency with only 46% of the vote, it would seem William Jefferson Clinton (1993) would be lame at best as he stumbled into his first few weeks and months in office. However, with solid majorities in both houses, Clinton’s lack of Washington connections and lack of a majority at the polls did not deter him. His wife’s highly-visible and highly-disastrous attempts at health care reform aside, this president still got his $1.5 trillion budget through faster than any of the above men save FDR, with the first-ever Family Medical Leave provision included, and through his authority as Commander-in-Chief, sent an impressive amount of military and emergency aid to Yeltsin’s Russia. Interestingly, the budget did not include a rollback of H.W. Bush’s tax increases, which is the single issue Clinton consistently beat Bush on in the campaign. Seems Trump is not the first to make bold campaign predictions, only to yawn and move on once elected. Here, by the way, we see another example of President Trump taking somewhat of a midway in the early road. Health care reform? Yep, but not the revolutionary and fundamental alteration of Hillary in ’93. Instead, we have today a proposal from the West Wing that seems to anger both extremes, but might just work for the majority in the middle. We say it might just.

Political Beast comes now to the man whose recent presidency is a splinter still underneath some of our readers’ skins. Of course, we could all quit picking at it and it would probably just work itself out on its own. Or we could use some of that stinky black ointment that supposedly makes it come out faster. Wait, what would the analogy be for the ointment? Ok, forget that last part. The point is: we all have strong feelings about this one as a matter of course, but, thank God, as controversial as George W. Bush (2001) was, his first month or so is pretty easy to describe: he brought back most of his father’s cabinet (like his father, he shuffled the deck quite a bit) and passed a budget that cut taxes by a larger amount and percentage than any president before or since. After his popularity post-9/11, he doubled down on these tax cuts by actually mailing checks to everyone in the country (whether they actually paid taxes or not), but in the beginning, his actions were simple: put Dad’s crew back in place, lower taxes. And it worked. Well, it worked as in it was all approved by Congress. Comparatively, Trump has done something similar in sticking to just one major piece of stand-alone legislation (health care reform), and a first-year budget with only half his agenda included. Elegantly simple, simply elegant, or just the work of a simpleton? There are other ways to describe it as well. I guess.

Time for the final POTUS in the mix. Of course, we said we were going to talk about modern presidents. Does Barack Obama (2009) really count as a modern president? In a world of Islamo-Fascism, the popularity of blatantly racist political parties in Europe, and the ability to disseminate information and disinformation globally in an instant, are we experiencing a post-modern political reality? The question’s been asked in some form or fashion since McKinley was president, so we’ll say “modern” and simply trudge forward. Obama caught some flack at first for his choices for Attorney General and Secretary of State, as well as EPA and HUD, but this resistance was mostly a result of a Republican realization that they had no power to slow down the legislative snowplow coming their way, so they took their puny stand where they could; during the confirmation hearings. In the end, they lost there as well. As for that legislative onslaught, it resulted in an expansion of CHIP, covering 4 million more children and pregnant women, and the passage of the Affordable Care Act. Interestingly, Obama’s first few executive orders (supporting the U.N. resolution on gender identity, rolling back international restrictions on abortion funding, and closing Guantanamo Bay) were quickly overturned or blocked after the Republican takeover of the House of Representatives in 2010, much like his ACA is being dismantled by the 115th Congress, currently in session. President Trump, ever the boisterously bombastic personage that he is, has mostly refrained from wielding the scepter of executive privilege in pursuit of his aims, maybe learning from recent history.

History. What did she teach us in the last 15 paragraphs? Hoover called Congress to task in a Special Session, Roosevelt flattered, Eisenhower compromised, Kennedy soft-pedaled, Johnson strong-armed, Nixon traveled, Carter scolded, Reagan got shot, Bush 41 budgeted, Clinton failed (health care) then aimed small (Family Medical Leave), Bush 43 kept it simple from the beginning, Obama focused narrowly and executive-ordered broadly, and Trump…? Well, President Donald J. Trump has no WWII like Truman, but has set himself up for an open budget discussion with Congress, like Eisenhower. Unlike JFK, our reigning prez has chosen to stick to his campaign priorities instead of softening his positions, and unlike LBJ, he has refrained from hard-nosed bullying tactics and threats to Congressional leaders. Dissimilar to Nixon, Trump hasn’t chosen to get out of the country, and hasn’t elected to pardon any of the high-profile folks in the political, military, or intelligence communities, like Ford and Carter did. Ronald Reagan’s two primary spending targets are alive and well in Trump’s budget: military spending increases and tax cuts, and Trump’s approach seems to dovetail nicely with H.W. Bush’s: achievement through passage of a compromise budget. Also, H.W.’s son shares a similarity with Trump, in that both Bush 43 and DJT proposed only one major piece of legislation (apart from a federal budget) in their first month in the Oval. As for a comparison with our youngest (and most popular) former-president, Trump hasn’t used executive privilege much, and hasn’t yet had anything overturned, but has had half of his cabinet and court nominees held up in lengthy confirmation hearings. Much like the Republicans under Obama, though, it seems the Dems and their delay tactics have a limited shelf life. We shall see. In the end, every president is their own person with their own style and their own administrative process. But that process gets clearer with perspective. Did Political Beast provide that perspective? And does the damage to the ship maybe look a little less bad from here?